Breaking News: the war for a voice

Originally published on 08/07/22 for UK-China Film Collab

According to the seminal French philosopher and media theorist Jean Baudrillard, one of the defining characteristics of the postmodern world is media hypersaturation. The “ecstasy of communication” induced by this saturation of media makes it so that the postmodern subject-that is, us as consumers of media- is perpetually in proximity to instantaneous images and information. These images distort the material world, becoming so prevalent that they take on a life of their own as simulacra- images derived from an “original” that are, via the process of saturation, divorced from their original contexts. Therefore, these images ostensibly provide a direct aperture into what they depict when, in fact, they exist as separate entities. This is evident in the transformation of the conflict between law enforcement and criminal activity into a form of voyeurism, whereby the ability of images to convince determines the outcome of these conflicts. One of many such crime-scenes-turned-media-circuses is the focus of Johnnie To’s Breaking News, which represents the microcosm of both a war between cop and crook and a war of conflicting images.

Much of To’s filmography hones in on ritualized social systems within both criminal organizations and law enforcement, accentuating the contradictions inherent to these systems by situating their inhabitants in scenarios where they are forced to choose between upholding these rituals or violating them. In Exiled, the archetypal Western band of outlaws is split between maintaining brotherly loyalty to a former member and adhering to a code of conduct by terminating him. In Breaking News, however, loyalties are fragmented as a conflict an undisciplined, disparate ensemble of cops and a duo of bank robbers escalates into a disordered struggle for survival. In the film’s opening, Richie Jen’s slickly charismatic criminal Yuen leads a bank robbery downtown. When the intervening police squad is swiftly dispatched in full view of a TV news unit, however, the priority of objectives shift from mere apprehension to restoring the tarnished reputation of the police force. A rendezvous between chief department members reaffirms what is already evident from the outset- it matters little whether or not the police were truly blindsided by the robbery as long as the image of humiliation produces a dominant discourse. In stark contrast to the rigid, unyielding materiality of the Election duology, where the engine of organized crime sustains itself on traitorous corpses and land acquisition, much of this film’s casualties manifest not in the form of tangible damage but in an alteration to a particular narrative.

Through situating much of the film in a run-down residential building, screenwriters Hing-Ka Chan and Tin-Shing Yip construct a struggle between both sides of the law for not just the attention of news broadcasters but for the cooperation of the hapless civilians residing in the building. The tension such a conflict entails is produced through To’s spatialization of friction, where cops clumsily barrelling down hallways is juxtaposed with the silent communication of criminals with civilians, hiding right behind a door that slips right under the former’s noses. The precision of David M. Richardson’s cuts in maintaining perpetual tautness, however, is disrupted by the erratic emotional currents of the building’s residents, whose naivety threatens to shatter the balance of power. In particular, the inimitable Lam Suet’s rendition of a bumbling father, Yip, contextualizes the position of the psychological conflict between Commissioner Fong and Yuen as one where civilians are collateral damage, subject to the whims of volatile egos. Moreover, Lam’s performance intermittently suspends the constant state of tension for comic relief- early on in film, he remains petrified at the sight of a gun sticking out from a holster, ignoring his unwitting son’s request for help with his homework. Yuen, only mildly irritated at the situation he has wound up in, exasperatedly gestures for Yip to go ahead and speak to his son. This gesture is slight, but it is representative nonetheless of an element of civility that runs counter the image the police attempt to project. Since interaction within the apartment is hermetically sealed, however, this is not configured into the images Yuen and his partner project to the media.

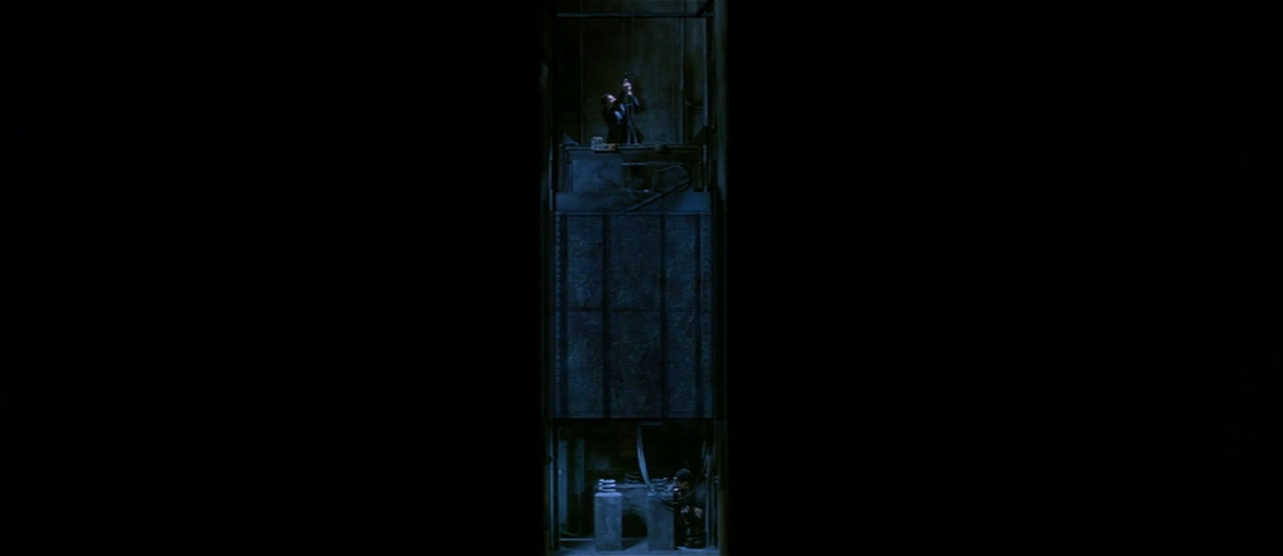

In capturing the succession of twists and turns in the course of one eventful day, To’s direction is necessarily concerned with the propulsion of momentum more than anything else. In stark contrast with the slick, concentrated gunplay characterizing To’s debut The Mission, Breaking News obfuscates its action to the extent where objectives metamorphose from maintaining images to survival, with cinematographer Cheng Siu-Keung taking full advantage of the film’s claustrophobic corridors to augment the threat of sudden violence. The carefully calibrated shootouts of A Hero Never Dies, which rely upon a foundation of geometric stability that melts into mists of blood and rain of broken glass (only to coalesce into another pristine composition) are replaced here by cranes and dolly shots that serve to severe the audience’s anchoring to the residential building. The minute scale of what occurs inside this building is amplified via the camera sweeping around the dense urban shrubbage of Hong Kong.

The film’s opening, in particular, is structured around a 7-minute single-take crane shot that uses meticulous blocking to stage the scene of a police bust, only to disintegrate into a hurried shootout. The seminal film theorist David Bordwell remarked upon the commercial obligations of To’s cinema as being precisely what enables him to translate his “pictorial intelligence” into cinematic form- there are few examples of this as clear as the denouement of Breaking News, where the visual cogency of apartment interiors is disrupted as Yuen escapes into the streets of Hong Kong (which culminates into a roadside shootout reminiscent of Heat), running frantically from the police squad on his tail, the camera establishing a rhythm of movement as agitated as Yuen himself. Here, To utilizes the sparse format of the 90-minute summer blockbuster as an avenue to explore the fragility of images constructed by news media, and how they obfuscate situations that have no definite moral alignment to reinforce the narrative of policing as a heroic institution. The “heroic mission” is therefore rendered as a mere farce.

Perhaps the defining sequence of Breaking News is the dual lunch that acts as the calm before the storm. Yuen and his partner, as both part of their efforts to win over the media and to satiate their own hunger, prepare a meal for themselves and their hostages. A camera broadcasting footage directly to a reporter depicts a scene of unexpected generosity, where civilian and criminal alike calmly share a meal with no threat of violence looming over them. In response, the intervening Commissioner Fong orders the preparation of packed meals for news agency crews. In this mirroring of actions, we observe wordless communication between Yuen and Fong- they may be on opposing continuums of action, but they will not tip over the balance when others besides themselves are at risk.

The distinctly masculine code of conduct, a hallmark of To’s filmography, is reconfigured here into one defined by the context of media saturation- in an environment where the creation and propagation of powerful images is universal and immediate, ensuring that there are no deviations from the script is paramount. Whilst this moment of tranquil reciprocation is not an outlier in To’s filmography (a similar respite occurs in The Mission), it does demonstrate precisely what makes Breaking News such a singular work: the reduction of entire social hierarchies into minute gestures, filtered through an omnipresent lens.