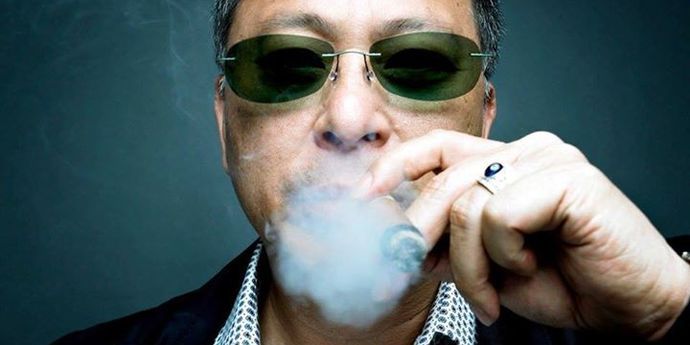

Johnnie To’s missions: stories of a Hong Kong film master

Originally published on 14/07/22 for UK-China Film Collab. Note, however, that the published version is an abridged version of a longer manuscript, which is available to read in its entirety here.

In 1997, John Woo’s third English-language American-produced feature premiered. Based on a spec script that had already been through a previous studio and a previous director, Face/Off opened to a largely positive critical consensus, though it would become the punching-bag of years of mockery for its melodrama and stylized mayhem. Woo’s first American feature, Hard Target, had become a battleground of warring creative sensibilities and cultural outlooks, particularly with regards to Universal’s overreaching interference through strict rating requirements and completion schedules. Woo was unaccustomed to such a degree of micromanagement, which was ironic, considering the impetus for moving to Hollywood was the opportunity for perceivably superior working conditions.

Hard Target, which opened to a lukewarm box office and critical response, was clearly a compromised project, which would later become evident when the release of the NC-17 workprint cut demonstrated the severity of the cuts demanded by Universal. In the same year as Face/Off, another Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicle directed by a Hong Kong pantheon director released. The inimitable Tsui Hark, who had directed what many would consider to be his magnum opus in the form of The Blade just 2 years prior, directed the critical and commercial bomb Double Team. Though Tsui would collaborate with Van Damme again on Knock Off a year later, his experience with Double Team deterred him from working in Hollywood.

In the 90s then, there is a clear pattern of stagnancy in Hong Kong action cinema induced by two of its best unsuccessfully trying their luck in Hollywood. Of course, this pattern does not reflect the industry’s output as a whole, considering how films in both the heroic bloodshed vein, such as Hard Boiled and Full Contact, as well as romantic odysseys, like In the Mood for Love and Green Snake, were largely embraced by both the home market and Western audiences. At the end of the millennium, however, a paradigm shift occurred with the release of a film directed by an artist now held in the highest of esteems: Johnnie To.

Prior to The Mission in 1999, much of To’s directorial work remained within the realm of television. To’s career in film began with his job as a messenger for the Hong Kong Television Broadcast Company, after which he ascended the ladder to become an assistant director on a TV production team, and eventually an executive producer.

According to To, his short-lived experience with TV productions was formative in that it acted as a “good training ground”-at the same time, he notes that it taught him about how commercial success superseded artistic quality in determining a film’s success. Though To was the sole director of his first action film The Big Heat, he attested to his lack of complete creative control over the project, pointing out how creative conflicts with producer Tsui Hark, combined with his inexperience in directing action for film, led to a compromised creative product. Prior to The Big Heat, however, To had collaborated with Chow Yun-Fat on a number of comedies, which is representative of how To’s collaborations with Wai Ka-fai would integrate his grasp over the spatiality of action with comedic elements. To Western audiences, the idea of Chow Yun-fat as an object of comedy or a romantic lead is a perplexing proposition, considering his reputation as a relentless cop in Hard Boiled, or a sage warrior in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Yet, in 1989, Chow played radically against type as a disheveled, hapless single father with a truly awful hairpiece in To’s All About Ah-Long. In a similar vein, the perception- and at times fetishization- of To as a filmmaker confined to making films about vengeful men with guns, which underscores the knotty implications of denoting To an auteur.

In 1996, however, To’s career took a turn with far-reaching consequences. In collaboration with Wai Ka-fai, with whom To had co-directed his most notable romcoms like Needing You and Love on a Diet, To founded Milkyway Image, an independent film production company. The trajectory of Milkyway is perhaps the strongest summation of To as a commercialist. Through the establishment of a rare creative synchronicity with Wai Ka-fai, To found an opportunity to continue dabbling in a wide range of genres and narrative structures at a time when many of his contemporaries, especially Woo, underwent artistic suffocation at the hands of a ruthlessly pragmatic industry. In his 2003 publication Planet Hong Kong, Bordwell noted that Wai’s role in co-directed efforts was largely that of a pre-production director, supervising screenwriting and conceiving narrative threads. In contrast, To is described as a distinctly hands-on director, with a great degree of interest in structuring the spatiality of shots. This allocation of roles therefore allowed (and ostensibly still allows) To to harness his strengths as a visualizer. Moreover, the founding of Milkyway Image was crucial to not just To’s success but to the industry’s as a whole- an year after the company was founded, administrative control of Hong Kong reverted to China. The intersection of this paradigm shift with the 1997 Asian financial crisis placed the industry in dire straits, incentivizing Hong Kong pantheon filmmakers like Tsui and Woo to seek greener pastures in Hollywood. Therefore, in an artistic landscape where commercial success became paramount to survival, To used Milkyway as a platform to continue directing Melvillean crime cinema that did not necessarily guarantee box office domination, from The Longest Nite to A Hero Never Dies.

The release of The Mission in 1999 is where To evolved into the filmmaker he is best known as today. A skeletal hangout flick following a gang of contract killers protecting a triad boss, the film’s narrative and structural simplicity is precisely what allows To to distill his mastery of shootouts with pristine clarity. Perhaps the film’s most famous sequence is a shootout taking place in a deserted mall, which is representative of how the economical quality of the film’s construction provides a platform for To’s formal experimentation. What is so enthralling about this particular sequence in a film full of taut firefights is the manner in which geography is presented and deconstructed. Beginning with the gang going up a pair of escalators, the shootout progresses with remarkable restraint-glances of suspicion are exchanged, guns are covertly drawn and someone inevitably ends up as a bullet-riddled corpse. When descending the escalators, Anthony Wong’s character glances towards the top of the second floor, anticipating another ambush. When this ambush does occur, however, the gang uses the way in which the elevator distorts line-of-sight to their advantage, swiftly descending whilst crouching to avoid gunfire. Through establishing the positions of every player involved, To creates a powder keg rigged to explode. Yet, at no point does the sequence metamorphose into the often histrionic (not necessarily detrimental) gunplay characterizing the cinema of other Hong Kong action filmmakers- through introducing hapless passerbys, To contextualizes this conflict against the backdrop of mundanity that his characters always try to distance themselves from. Moreover, such sequences disrupt not just spatial structure but the relationships between these characters. Whether someone decides to take cover and how they tackle (or refuse to) disruptions to their hermetically sealed sphere of camaraderie has permanent consequences for the structure of the group. It is not difficult to deduce why The Mission is one of To’s most highly acclaimed works in the West- its visual asceticism and emotional centre of professionalism colliding with brotherhood evokes Melville and Mann respectively, rendering it a much easier proposition to digest than any of To’s comedies.

The success of The Mission internationally (where it was screened at both Berlinale and TIFF) acted as an introduction to To for most Western audiences. It also consolidated the two-track production system that Milkyway would proceed with from thereon: whimsical romantic comedies starring Cantopop idols like Andy Lau, and the slick, often nihilistic action thrillers that are most commonly associated with To today. Whilst these categorizations are a useful way of understanding how Milkyway was able to maintain diversity in the range of films they produced, it is important to note that these categorizations are also largely arbitrary, based on an attempt to separate what To is known for in the West from the films that act as box office draws in Hong Kong. There are few clearer examples of this than Running on Karma, To’s examination of faith confronted with the inexorable presence of fate. Much of the film revolves around the often darkly comedic escapades of Andy Lau, clad in an absurdly noticeable muscle suit as a clairvoyant monk-stripper going by the name “Big”. Yet, the sincerity with which To approaches Big’s position in the world renders the film less a comedic farce than an often moving exploration of predestination. Its synthesis of genre is such that its transitions between police procedural, screwball comedy and spiritualist action movie never serve to dis-anchor the viewer from its thematic foundations- even when it focuses on Andy Lau and Cecilia Cheung simply walking the streets of Hong Kong, a certain sadness looms over the scene.

The blessing-or curse, as it later turns out- of prophecy that Big possesses pushes him towards the role of the modernist hermit, abandoning his life as a monk so as to avoid confronting the omnipresent spectre of death. Therefore, the compartmentalization of professional and personal lives that To’s triad gangsters and cops engage in is translated here into a compartmentalization of materiality and spirituality, which allows Big to avoid the moral implications of clairvoyance in much the same way as Lok in Election avoids acknowledging the ethics of his ascendance. In both films, the use of brute force as a way of negotiating with the erratic quality of modernity- Big quite literally inflates himself with capitalistic excess, developing a physique that conceals his identity as a monk, whilst Lok steamrolls over the intricacies of the triad election system by bashing his last competitor’s head in with a rock. The difference, however, lies in what both characters confront: Lok confronts the unpredictability of an ostensible democracy, whilst Big confronts the inevitability of tragedy plaguing everyone he has ever known. Though both Running on Karma and Election exist in drastically different formal modes, both of them are also representative of the direction To’s work would take, with the Milkyway two-track system extending the nihilism of To’s crime dramas and the warmth of his romcoms into the realm of postmodernism, in the form of Drug War and Romancing in Thin Air respectively.

In discussing To as both auteur and gun-for-hire modes, it is paramount to locate his relationship with Hong Kong and its depiction in his films. Unlike some of his contemporaries, To chose not to explicitly align himself or his work with a distinct political entity in the aftermath of the 1997 retrocession, nor has he recentred his commercial operations to either mainland China or Hong Kong. As is evident in his Cantonese and Mandarin productions, To’s films are situated in both mainland China and Hong Kong, and, as in the Election duology, shift between both regions in the span of a single film. It is therefore all the more impressive that he continues to finance his films from both regions whilst also commenting upon the political currents of Hong Kong-RoC (Republic of China) relations in implicit and, rarely, explicit forms.

As deliberated upon earlier, much of To’s filmography is centred on professional law enforcement and criminals, and their attempts to navigate through the blurring of the professional with the personal. Beyond the duality of law and order, however, To and the Milkyway Screenwriting Team often hone in on the contradictions inherent to other professions as well, such as healthcare in Help! and Three, in addition to corporate hierarchies in Office and the Don’t Go Breaking My Heart duology. These films revolve around Hong Kong encapsulated in microcosms of crisis, such as in Three, where the interests of medical professionals are interlinked with that of both criminals and law enforcement. Similarly, in Breaking Newsa residential building in Hong Kong becomes a battleground of warring media images between cops and crooks. To therefore situates Hong Kong on the perpetual verge of disaster, which is accomplished through presenting political conflict in spatial terms. Whilst his films do not necessarily comment directly on ongoing political affairs (barring the Electionduology, which could be interpreted as a critique of the presumed superiority of liberal democracy over authoritarianism), there exists a certain undercurrent of cynicism in much of his late-period work, which transposes the moral quandaries of his 90s neo-noirs to the lives of ordinary people in contemporary Hong Kong. In particular, Life Without Principle posits the 2008 financial crisis as the precedent for exploitative violence- instead of the more visceral forms of violence enacted in his crime thrillers, however, the violence is structural, predicated on the basis of an already unstable financial system. When the market enters a state of freefall, those dependent on it to rescue them from debt are brutalized in the most detached of fashions. Here, the threat of violence is communicated not in the form of distinctly masculine aggression but in the form of numerical data, presented in bar charts in symmetrical, pristine offices. If a consistent thread of inquiry is to be identified in To’s crime films from Breaking News to Drug War, it is that the dominant mode of neoliberalism that governs Hong Kong’s economy is not necessarily any better than the RoC’s state authority that is so commonly demonized. Yet, in Drug War there is a clear denunciation of the myopic state-enforced War on Drugs that is doomed to end in futility.

In an interview with Filmmaker Magazine in 2008, To was asked by interviewer Nick Dawson whether he considered himself an “auteur”. To responded with “‘Auteur’ is such a big word. But I think nothing matters more than making a film that reflects who you are as a person.” Much has changed since then, not least the commercial market within which To operates (which is, as many commentators have described it, on its last legs in a post-COVID environment). What has not changed, however, is To’s status as one of Hong Kong’s most highly esteemed filmmakers- one need only note his contribution to the upcoming Septetanthology alongside Tsui Hark and Ringo Lam. The proliferation of a range of retrospectives, showcasing both the crime films he is most commonly known for and his collaborations with Wai Ka-fai, have served to only heighten his popularity in the West- although he is not as evocative to the average filmgoer as, say John Woo, Election and PTU are often cited as hallmarks of 21stcentury crime cinema, though with a certain air of condescension that regards them as superior to less tonally consistent works like Mad Detective. What remains less clear, however, is whether his commercialist tendencies render him a creator of populist entertainment or a creatively distinct “auteur”. In an interview with MUBI Notebook in 2017, curator Shelly Kraicer (who, along with Bordwell and Stephen Teo, was one of the earliest to interview To and denote his cinema a distinct entity) noted how To often forgoes storyboarding and elaborate scripts in favour of spontaneity, paying particular attention to the spatial construction of scenes and how the action taking place within them is choreographed. The construction of these scenes is therefore rendered distinct by To’s focus on spatiality, even though his mode of production is neatly organized into films designed to attract a massive audience and more “personal” films that do not necessarily need to be commercially viable. It then becomes evident that an evaluation of To’s authorial characteristics requires an abandonment of labels as shaky when lifted out of a Western cultural context as “auteur”. In directing and producing a wide palette of films under the Milkyway banner, Johnnie To is undeniably a commercial artist, but that does not mean his auteurism is any less distinct than that of an independent filmmaker.