Miami Vice

Originally published on 27/09/2020 on Letterboxd

In a career punctuated by undeniable commercial and critical successes such as Heat, but also more divisive features that would be regarded by most as commercial failures and critical bombs, Michael Mann has always revolved around the periphery of mainstream acclaim rather than in it centre-which is puzzling, considering the fact that his films typically star pairs of guaranteed box-office draws (from Al Pacino and Robert De Niro in Heat to Johnny Depp and Christian Bale in Public Enemies). Sandwiched between filmmakers who are commercial titans and pariahs of mainstream criticism like Michael Bay, and more conventionally acceptable individuals like Steven Spielberg, Mann occupies a position that few auteurs, experienced or amateurish, can occupy: a Murnau of the multiplex.

Yet, from his stylistically-definitive debut feature Thief in 1981 to his Academy-Award nominated Pacino vehicle The Insider in 1999, Mann was hailed as, if nothing else, a master of action cinema at its peak. What’s more, his status as producer of the ground-breaking police drama Miami Vice in the 1980s cemented him in the collective psyche of the pop culture realm.

Today, however, Mann’s status has undergone a state of dramatic flux; no longer regarded by mainstream audiences as a bastion of artistic respectability, Mann, through his full-fledged leap into the digital medium with Collateral and further exploration of it with his latest, Blackhat, has embodied the “vulgar auteur”: an artist whose commitment to their very particular style of craft offends the sensibilities of the mainstream. What drove this paradigm shift was an evolution of the medium of film as a whole: the shift to digital video as a successor to film. No better is the monumental impact of this transition illustrated than in the film I firmly believe to be his magnum opus, Miami Vice.

Adaptations of television shows into film have been defined primarily by failure; some, face commercial and critical disappointment but garner a steady stronghold of fans, whilst others are generally reviled across all ends of the viewership spectrum. What seems to separate the reception to both of these categories is faithfulness to the source material; the former example maintains the tone and general episodic framework of the television show, whilst the latter revises much of the details that endeared fans of the original series. Miami Vice falls into the latter category, explaining much of its critical failure. It would, however, be amiss to call one of the most stunning films of the 21st century a mere “adaptation”.

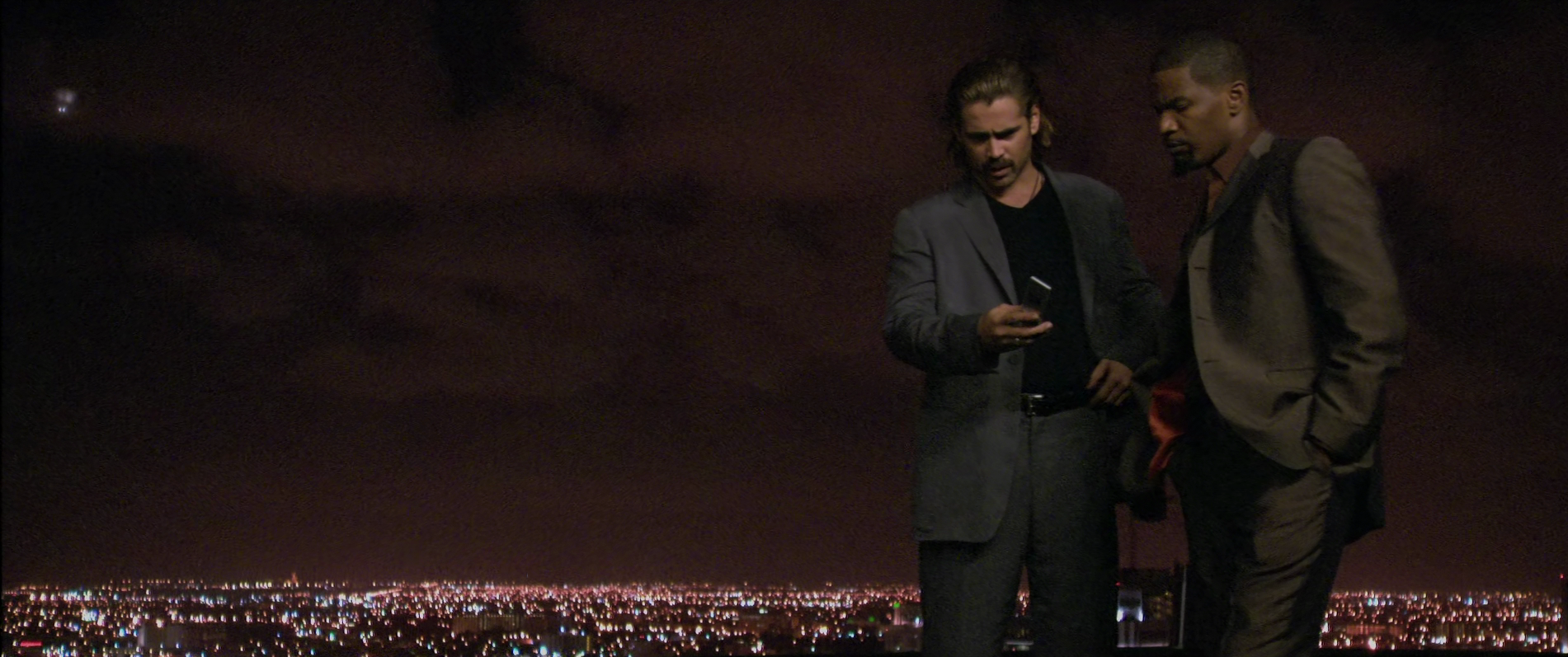

In Miami Vice, Mann takes the most basic bones of his television show-two vice cops solving crimes in Miami-and twists them into something thrillingly, even intimidatingly, new. No longer are bright pastel colours, stark white suits and pet crocodiles the milieu the protagonists of the television show, James “Sonny” Crockett and Ricardo Tubbs, occupy; instead, a palette of earth tones (something that Mann made sure to avoid in the production of television show), faint neon hazes and violent grit define the 21st century world that Crockett and Tubbs have been transposed into. Even the wardrobes of the duo reflect this stark evolution; cool linen pants and pink silk shirts are replaced by gaudy Ozwald Boateng suits and striped shirts. It should not be assumed, however, that this reimagination falls into the rather juvenile notions of “reimagination” within a framework that maintains “adult” aesthetic sensibilities but lacks a soul. Indeed, this reimagination is not merely an aesthetic one, but also a thematic one; the compact, individual trades of drug shipments and slick escapes in Ferraris have been replaced by a confrontation with the grim realities of drug trafficking inherent moral grayness of undercover policing, where the lines between cop and criminal are ever blurred-after all, in a world where entire societies evolve overnight, what are professions if not temporary roles to be played and abandoned at will? Dion Beebe’s mesmerizing cinematography distils this uncertainty into the twilight skies, not day nor night, that loom forebodingly over Crockett and Tubbs, and the hurricane hanging on the edges of the Miami skyline.

Miami Vice’s cinematography is perhaps its defining trait, one that was noted and admired by even its staunchest critics upon its releases. Employed in capturing the claustrophobic environments of 2004’s Collateral (another defining digital Mann), Dion Beebe returned for Miami Vice in to craft what is perhaps the most stunning mainstream American film of the 2000s. What many would call a premature employment of the digital medium (which had been employed by Robert Rodriguez and George Lucas as well) is what is rightfully called by defenders of the film as a deliberate (and successful) attempt to capture the ever-moving currents of people, money and light that populate the film in all their stark and uncomfortable glory. The opening scene of the theatrical cut (which immediately sets both the tone and clarifies the time period through a Jay-Z/Linkin Park Encore needle-drop). Audiences have absolutely no idea who any of the individuals onscreen are supposed to be-there is no indication of who’s the cop and who’s the criminal. This, of course, is all a deliberate blurring of divisions by Mann in order to make audiences feel the same disorientation that characters in the film do, as violent things happen fast and without warning, leaving the shadows of ethereal connections in their midst. Families are destroyed, and men destroy themselves through leaping in front of speeding trucks, leaving trails of blood, not unlike the trails of foam and motion left by go-fast boats. The action, the fleeting moments of the individual altering the collective-that matters more than the result of what happens. Time is luck-luck runs out.

The lead performances reflect this focus on process rather than outcome; in particular, Colin Farrell’s (career-best) turn as Sonny Crockett expresses an internal turmoil almost entirely through grunted one-liners and sad, puppy-dog-like eyes. You could call it “shallow” or “unimpressive” to maintain that level of stoicism in a film with performances as gleefully hammy and scenery-starving as John Ortiz’s maniacal antagonist, Jose Yero-or, you could view (as I do) Farrell’s performances as yet another key element of the distinctly Hawksian characteristics of the film as a whole, demonstrating a deeply world-weary resignation to the grim realities of his profession, countered by the romanticism of the possibility that maybe these roles don’t have to define the characters that occupy them. Jamie Foxx is similarly restrained, although more conventionally impressive, in his turn as Ricardo Tubbs. The various supporting performances punctuating the film, from Naomie Harris to Gong Li, create a world that is coldly functional in nature but always on the verge of collapse.

Mann’s status as perhaps the finest action director of the 21st-century American mainstream (even rivalling masters of the craft like John Woo) is evident throughout the film, with the intentionally jerky and energetic camera, splattered with blood and flailing around not unlike the many bodies that drop to the ground in the film’s climactic shootout. Yet the blinding flashes of gunshots cannot hide the cold, passionless violence that dictates transactions. The moon shines through the shattered windshield of a car; bodies lie gray and ethereal, unmoving except for the bursts of gunfire that pierce through them. The cyclical path of destruction in the flimsy dichotomy between those on the side of law and those on the side of crime results in those closest to the protagonists being abducted, tortured and (as the final few frames of the film hint at) possibly dead. Civilians entrapped in undercover operations are powerless to do anything but stand, as their families and lives collapse-all that they know is the few obtusely conciliatory phrases uttered by those that are supposed to protect them. And so they run into the night, hoping that they will be freed from their painful mortal coils by an incoming car. All that is left is a trail of blood, reflected in the hellish red of the hurricane-plagued sky. Exchange upon exchange, a never-ending transfer of drugs and information-through tinted windows, and through phones. The truth does not even surface in face-to-face conversations-because after all, are even the roles we occupy the “truth”? Or are they simply all we know how to do, because we are afraid to confront the possibility of doing anything else?

Writing about Miami Vice would be futile without deliberating upon its ending, an aspect that unfortunately seems to be overlooked by even many of its defenders. Two characters stand at the end of a beach; the storm has ended, and this is its aftermath. They know that there will be a boat arriving shortly, and that it will separate them. They know that they will never meet again because no matter what they share, the roles that have torn them apart are too powerful to overcome; transactions override everything. Even the momentary escape that they made from these roles collapses into revenge and its bloody aftermath. They share a final exchange:

“Time is luck”.

“Luck ran out”.

The boat arrives. The camera zooms towards them, trying to keep them together even as the boat slowly fades away. Crockett stands at the edge, gazing in what appears to be a swirling hurricane of regret and melancholy. And then, he turns away, and walks back-as if nothing happened. The film cuts to an inverse of this relationship- a reunification, rather than a separation, across the mortal and the ethereal realms. Two hands hold each other, but the camera freezes-even this reunification is impermanent. A face looks towards, hair rippling in the wind, on the verge of tears. They take a breath, and gaze in uncertainty at what is to come. A man walks into a hospital, around which are littered the shadows of nurses.

Miami Vice does not end on a note of certainty-it does not consolidate the fates of its characters, because nothing is permanent. When not even the future is uncertain, all that matters is the here and now-speedboats in the night.