On Damnation, Hellfire and Other Such Irrevocable Facts Concerning the Mortal Vessel in Oppenheimer

“It’s the bomb that didn’t go off. The threat that no one knew was there- that’s the bomb with the real power to change the world”.

-Tenet (Christopher Nolan, 2020)

“I am banished from the patient men who fight

They smote my heart to pity, built my pride.

Shoulder to aching shoulder, side by side,

They trudged away from life’s broad wealds of light.

Their wrongs were mine; and ever in my sight

They went arrayed in honour. But they died,—

Not one by one: and mutinous I cried

To those who sent them out into the night.

The darkness tells how vainly I have striven

To free them from the pit where they must dwell

In outcast gloom convulsed and jagged and riven

By grappling guns. Love drove me to rebel.

Love drives me back to grope with them through hell;

And in their tortured eyes I stand forgiven”

-Banishment (Siegfried Sassoon)

“The universe is no narrow thing and the order within it is not constrained by any latitude in its conception to repeat what exists in one part in any other part. Even in this world more things exist without our knowledge than with it and the order in creation which you see is that which you have put there, like a string in a maze, so that you shall not lose your way. For existence has its own order and that no man’s mind can compass, that mind itself being but a fact among others.”

-Blood Meridian, or, the Evening Redness in the West (Cormac McCarthy, 1985)

The first time I can recall thinking what it must feel like to die was when I was 12 years old. What first initiated my initially academic and then more intimate fascination with death was not the kind of death that might befall most of us- perhaps the heart fails to serve its purpose, or perhaps the body simply abandons the will to continue where the soul retains it.

No, that fascination stemmed from what felt like a rather momentous discovery for myself at the time- the discovery of what a black hole was. My burgeoning interest in astrophysics never truly progressed into the mathematical realm, but I can still remember what it felt like- that is, to discover that there are innumerable worlds beyond this one, not just beyond the stars but embedded in every living creature’s tissue. I could never hear the music that guided molecules to collide with and combine with each other, as so many others could, but I nevertheless found myself transfixed by the undetectable presence of vestiges and afterimages of the orchestral compositions of the universe.

The black hole is an entity of a magnificent and horrifying strength, a parable of theory rendered tangible, an antithesis to our already tenuous grasp on the fundamental structures that comprise a world where-in the words of Marx and Engels- all that is solid turns to air, and all that is holy is profaned. Its existence is an affront to any and all facile doctrines that maintain a universality of substance, and yet to know that it exists-however far away-is to affirm a kind of belief in an unknown that exists beyond our myopic laws of time and space. The otherwise steadfast delineation between the divine and the scientific collapses into itself in a manner not unlike the process that births a black hole. Even the very term “black hole”-already seeming a childish attempt to define that which transgresses the bounds of understanding- is something of a misnomer in and of itself, since they are not innately entrances and exits to other worlds or indeed to anywhere at all. As a star at least 25 times larger than the sun collapses due to a lack of nuclear fuel, its death is commemorated by the funereal fireworks of a supernova. Supernovae, in turn, signal the collapsing of 5 to several tons of solar mass into what is referred to as a stellar-mass black hole- that is, one that is created by the gravitational collapse of a star.

The multi-hyphenate public emissary of the heavenly bodies (as well as astronomer) Carl Sagan once referred to black holes as “apertures to elsewhere”. These apertures were not constrained by fuel or distance or even time itself- they could, ostensibly, lead to another epoch entirely. But if one were to go down this tunnel to Wonderland, Sagan wondered, would there still be “Alices or white rabbits”? Admittedly, I was not so much drawn to the potential opening of gateways beyond space and time as I was to the destructive capacity of black holes. I tried to ascertain what might happen to the body when it entered beyond the event horizon, and in what ways the molecules that comprised a somewhat pudgy pre-teen such as myself might rearrange themselves. Perhaps they would, as much of the public consciousness imagines, reshape themselves into spaghetti made from flesh and blood, dispersing strands of meat across the blackness of the void. Maybe the changes would begin from within rather than from outside, as my already brittle bones shattered and melted into a primordial soup, and my muscles atrophied and deflated, sending a shriveled sheet of keratin and epidermis across a Lovecraftian abyss until it turned into dust. I tried to envision what I would hear and see as I was irreversibly drawn into an entity that refused entry to even light- would those final, momentous sounds be the whispers of a loved one, desperately conjured by the mind to try and cope with imminent disintegration? A soundscape of shrill, acerbic white noise seemed a likely possibility.

Night after night, I was held awake by the vice grip of unanswered questions. Wanting so badly to know what lay beyond a black hole, I searched for answers in every source, even attempting to peruse Volume 2 of Theoretical Astrophysics, Stars and Stellar Systems. The fact that I had not even begun taking specialized classes for physics, let alone been formally introduced to astrophysics as an academic specialization, did not act as an obstacle to what eventually developed into an obsession. This search was not part of a wider ambition, as so many of my peers held at the time, to venture towards these very cosmic realms as an astronaut. Beginning to even consider the possibility of becoming one was impossible, as primal fear shut down any such ambitions- a hole in my spacesuit would lead to a re-enactment of Cronenberg’s Scanners, a tear in a cable connecting me to a space station would prompt a plummeting into nothingness and before I even entered the space shuttle my heart would fail from a sudden wave of panic. What I perceived as a fundamental inability to rise more than a couple feet above the ground, however, only fuelled the paranoia that would accompany me for the rest of my life after this obsession- that paranoia, specifically, being the hostility of the universe to allowing itself to be understood, and the cruelty with which humanity’s boundless and unquenchable desire for discovery would be quelled by sudden visitations of atrocity upon those most removed from responsibility. I was, on a primal and instinctive level, terrified of something I couldn’t see, and which I only discerned traces of in the wrinkles and graying hairs that would manifest in those around me. I sought an escape into the cosmos knowing full well that the thrill of seeing what no one else could would be followed by a swift and brutal demise, and in retrospect I think I desired the latter as much as I did the former. The sickness that was my failure to comprehend an ontological stability was, I felt, radioactive, and it was something that I feared would kill me far more swiftly than even entering a black hole.

As I grew older (though far from wiser), I became preoccupied by fears that were far pettier and less consequential than those that haunted me at age 12. What remained constant, however, were the sudden and unwelcome occasions upon which I would envision myself in my twilight years, losing my grip on my motor control and my mind. Even at my happiest, the intrusion of fear in the form of a timer told me how many years I had left to live, suggested possibilities of a premature death and laid out (in painstaking detail) all the possible ways in which time would whittle away into oblivion and I would be left an old man, full of regret and still oblivious as to what lay beyond a black hole. In dry psychiatric terms, it might be suggested that I had “anxiety” and was plagued by “intrusive thoughts”, but no amount of pathologizing could answer (at least at the time) why I felt so perpetually seized by mental tapestries of rapture. Living in a country that seemed to lack abundance in any respect except for military and nuclear might, the thought of nuclear war had always seemed an inevitability- perhaps it would take decades for Pakistan and India to reach that endpoint, but it would happen one day, and it would begin from the psychotic episodes of rabid jingoism that seemed to arrest even some of my peers. Flayed skin peeling from fabric burnt into flesh, pastures of rubble fertilized by radioactivity and life-destroying mutations generations later were, I assumed, simply future textbook additions that would be described in the same centrist, noncommittal terms that our textbooks described Pakistan’s own sordid history. Though I remained transfixed by the black hole, my overwhelming fear of its destructive capabilities was replaced by a fear of what would occur not light-years away but in my very backyard- no matter the form (or indeed formlessness) these fears took, the fear that an imminent and unannounced demise was never quite far enough to take solace in its not having arrived lingered. The wide-eyed fascination that had gripped me as a child, the desire to know what lay beyond the bounds of matter and light, the maniacal obsession with the intangible forces of entropy that seemed to announce themselves galaxies away- all of what had transfixed me slowly but surely mutated into a winding vortex of abominations that were too terrible to gaze at with anything but revulsion, and yet too terrible to tear my eyes away from. No matter how hard I tried to stop looking, to stop tormenting myself with recurrent fantasies of self-immolation at the edges of supernovae and soundless screams in the depths of black holes, to resist giving into fear itself, I found myself too incontrovertibly paralyzed with terror by the existence of the inhuman machinations of worlds that existed before life first emerged on Earth.

Since the first time I thought about what it must feel like to be ripped apart atom-by-atom and feel one’s very being melt away into a fine dust, 9 years have passed. My relationship with death has taken on a quality not unlike that between colleagues in the workplace- I greet it each morning with the rigor mortis of a smile that I piece together to reach the end of the day unscathed, and scarcely exchange words with it except for the most mundane of affairs- for instance, would the very act of writing these words contribute to an outcome that, were I to die in 5 years time, resemble a suitable summation of my nearly 21 years on this planet? The desire for self-destruction has dissipated into a form that is far more manageable, and yet more tangible- it manifests in an onus to begin the cycle of fear to blade, blade to skin, skin to rows of bleeding lines, bleeding lines to faded scar, faded scar to skin once again. Ambitions once lit with the fire of a thousand suns and seeming impervious to anything except the will of divine entities have since then been quelled, not unlike the failure of dwarf stars to become black holes, despite fulfiling every other requirement that transforms supernovae into black holes. They have become aberrations in an otherwise utterly resigned mortal vessel, one that seems propelled towards the future by little else than a desire to see the next morning. Experiencing the discordant rhythms of Christopher Nolan’s latest multimillion-dollar experiment in operatic scale and reconfiguration of emotional multifacetedness into engines of brute force, Oppenheimer, reawakened these latent fears in a manner that little else in recent memory has.

In a fashion unlike much of his past oeuvre, Nolan (along with the impeccable Jennifer Lame who, along with Hoyte van Hoytema and Ludwig Goransson, have expanded the spatial and auditory bounds within which Nolan’s form typically ricochets to one in which it is seemingly boundless), opens Oppenheimer with not an in-media-res immersion into a landscape of overwhelming sound as in Dunkirk and Tenet. Instead, the only absolute truth that is affirmed throughout the film’s entirety arrives before we first gaze into J. Robert Oppenheimer’s steely blues- reflective pools of light that seem to house not even a spark of hope behind them. This affirmation takes the form of a primordial coda, one that recalls the Original Sin of theft from Eden that cast humankind down to Earth in the first place- the myth of Prometheus.

“PROMETHEUS STOLE FIRE FROM THE GODS AND GAVE IT TO MAN.

FOR THIS HE WAS CHAINED TO A ROCK AND TORTURED FOR ETERNITY”

Exclaim the clouds of explosions that leave no illusions as to what the film might declare to be the titular physicist’s lasting contribution to humanity. Deliberations on its condemnation of Oppenheimer or lack thereof are futile when the incontrovertible legacy of plumes of nuclear fire seem to cast so tall a spectre over his life. Yet, where this Malickian expression of indeterminate, all-encompassing terror might strike a permanent path of ritualistic condemnation and self-loathing in the work of a filmmaker less obsessed with the singularity of a figure like Oppenheimer, Nolan’s film continues to perform the unthinkable for a filmmaker with his precedent- it establishes a dialectic between not just subjectivity and objectivity, past and present but between states of matter themselves.

Humming just underneath the surface of the ordinary, material manifestations of forces of attraction and string theory disrupt the recognizability of the all-too-familiar biopic structure that Lame lures us into believing that we are about to witness. Yet, this is not a tale of tortured genius or of a Cassandra of the subatomic realm- though Oppenheimer’s near-prescient grasp over the principles of a science that hadn’t fully come into being is evident, it isn’t his genius that the film is concerned with. Instead, fear is the most instrumental of all unseen forces that seems to guide Oppenheimer. Eyes wide open, scarcely illuminated by the glow of moonlight, rain pattering against the window, droplets hammering against the ground, droplets turning into the faraway slamming of fists against wood- these are the rhythms that comprise the first 20 or so minutes of the film, which form a sensorial portrait of Oppenheimer succinctly enough to the point where the director’s usual affinity for expository spiels seems almost completely extinguished. The classicism that his form exhibits within the first act (or at least whatever comprises a first act in a film that defies structural categorization as much as this does) is suffocating enough on its own, using the textural sterility that has been exhibited in much of his work since Inception to evoke a dreadful uniformity that sows the seed for the physicist-to-be’s initiation into the similarly featureless realm of the military-industrial complex. But this textural differentiation, as opposed to what might be expected from biopics more turgid than Nolan’s, is pierced by what seem almost to be transmissions from the subatomic world, encroaching upon the very structure of the biopic to impose a kind of cosmic horror over the proceedings of a legal thriller. Beyond purely its suggesting of Brakhage and Solomon, the penetration of these images into the structure of Oppenheimer presents a thrilling possibility for the late-period evolution of an auteur- from narrative to experimental film.

In the most intellectually rigorous deliberation upon the legendary director’s work, John Ford: The Man and his Films, the inimitable Tag Gallagher recalls a conversation with the similarly singular Jean-Marie Straub, a titan of the experimental form and whose- pertinent to this essay- own collaborations with Danièle Huillet often isolated historical allegories from their socio-linguistic context, particularly in the case of Antigone. Gallagher noted that in his interaction with Straub, he asked the latter what he thought an experimental film was. In response, according to Gallagher, Straub enthusiastically slammed the table and declared “The Long Gray Line! That’s an experimental film, no?”. Notwithstanding the temporary bewilderment that someone less familiar with Ford might have at hearing a Fordian biopic being termed “experimental”, Straub’s denotation stands out as an example of remarkable prescience- not just in consideration of Gallagher’s own deliberations on the pioneering structural reformations of Ford’s oeuvre later on, but also because it fundamentally obliterates arbitrary divisions of genre that might otherwise limit the consideration of Ford’s film as anything but a masterwork of the highest order. Within Ford’s own films, the proceduralisation of history and its conscious construction as dioramas laced with artifice are consistent concerns that only grow more saddled with the weight of American generational atrocities over time. In The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, a work laced with the hopes, fears and uncertainties of an entire community, the twilight showdown between the timid, urbane lawyer Ransom “Ranse” Stoddard (Jimmy Stewart) and the infamous outlaw Liberty Valance is a confrontation that resembles less a triumphant victory of the downtrodden over the destructive than it is a succumbing to the inescapable tides of history. Through the lens of memory, a busboy still clad in an apron emerges out of a saloon, the doors still swinging in cyclical motion as his opponent emerges, already donned in both the garb of a victor. Hunched and already seeming armed and ready to embrace death, Ranse reaches for his revolver in a series of cuts that suggest his miraculous triumph over the outlaw who stripped him of his pride and dignity. Embellished as the liberator of a community and a legend of the West in his own right, Ranse’s inclusion in the annals of history is almost imperceptibly swift. To document his veneration would be of little value when the suffix of “Senator” to his name in the film’s opening already cements the invaluable nature of this transformation.

But as Ford’s funereal Western makes clear, Ranse’s lionization and his eventual accession to power in the US government is not a tale of a man making his own fate. Instead, as the climax makes evident, the man who shot Liberty Valance was not the Senator-to-be - instead, the shot heard across the town of Shinbone was fired by Tom Doniphon (John Wayne), the town’s unofficial last vanguard against Valance’s raids before Ranse stumbled along. As a Western wrestling with the slow but sure death of the conditions that made the Western possible, Liberty Valance is amongst Ford’s most elevated accomplishments as an artist, acting as a culmination of the construction and implosion of the very mythologies of the West that he was so instrumental in reinforcing. Beyond his oeuvre, however, the film pointedly construes the indiscriminate codes of bloodshed that ran through the veins of the West and the system of organized, democratic federal government that suppressed it as one and the same. The very embellishing of the past, Ford posits is thus inextricable from the enforced erasure of historical record through the snuffing of the truth. As is reflected with such dilated, sluggish temporality in The Long Gray Line, these revisions need not conflict with any existing historical record, since the endless 21-gun salute of history absolves and repudiates the legacies of those who shape it. Ford’s film thus arrives at the conclusion that the hand that pulled the trigger is a virtual nonentity- it matters not the motive nor the mission that sent a bullet barrelling into the heart of Liberty Valance. Instead, the act has an agency of its own that is at once divorced from the mind behind it (in that Ranse is venerated as a hero despite being mere seconds away from becoming a victim, were it not for Tom) and inextricably bound to the very soul that engineered it (in that the phantom of the man who saved Tom’s life and thus also forces upon him the legacy of a killer, albeit one- in the age-old American fashion- who is celebrated instead of punished).

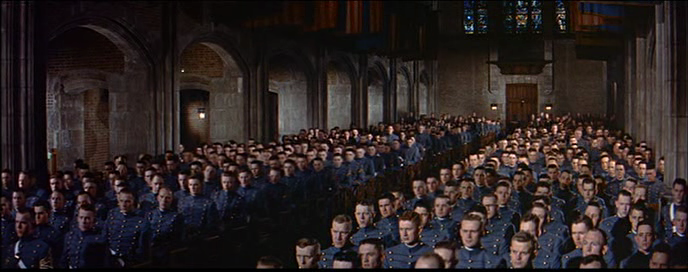

With The Long Gray Line, Ford’s weaving of a community bound by mythologies of law enforcement and its corresponding disorder- in this case, the military academy of West Point instead of a dying Old West town- unfolded on a plane far more ambitious in scale than perhaps even How Green Was My Valley. Framed through a conversation between the aging Marty Maher (Tyrone Power) and President Eisenhower, Ford’s near-biopic navigates Marty’s journey from one of an indistinguishable mass of Irish migrants arriving on American shore in 1898 to Master Sergeant at West Point 50 years later. As Ford’s first and only film (notwithstanding his segment in the anthology How the West Was Won) shot in CinemaScope, there are few of the ochre vistas and endless fields of green that might be identified in The Searchers and The Quiet Man. Instead, Ford used the very medium he once denigrated as a canvas shaped like a tennis court to bring to the surface the very barrenness of West Point as both an institution and as an engine of death. For a film so full of youthful, boyish camaraderie amongst an often hapless Marty and his comrades at West Point, The Long Gray Line is as much a work concerned with the death of the figure at its heart as it is with his life- often in an almost outwardly Brechtian form, as is so painfully evident in Marty’s declaration when he first enters West Point- “What a fine ruin it would make!”. Throughout Marty’s discovery of brotherhood and a devotion to a cause beyond himself at West Point, there exists the spectre of the military parade- be it his reuniting with his temperamental father or his torrid marriage with Mary O’Donnell (Maureen Hara), there are seemingly immovable hierarchies of authority which dictate that Marty should remain forever a totem for West Point’s cadets to embody, even as the man the US military shapes Marty into grows increasingly distant from the man he once was. Each military parade that Marty joins throughout his life ushers him into another, irrevocable stage, and yet he remains firmly, inescapably rooted in West Point, even as the men he grew up with die in battle and he takes on the task of recording their losses in yearbooks.

As West Point resembles more and more a mausoleum, the film takes on an expressionistic quality that is paradoxically defined by its very rigour. The grounds of West Point are suddenly but surely overridden by automobiles that, no matter the humming of their engines, cannot hope to match the slamming of boots upon soil, the latter of which is a sound that seems to echo more and more unsettlingly across Marty’s life as he grows increasingly and inseparably enmeshed with West Point itself, as if a ferryman carrying bright-eyed young men across the River Styx. In a film where the sudden onset of tragedy is at constant odds with the environment’s demands for perpetual rejoicing, there is no sequence that better embodies than this dialectic than Mary’s death. As she grows weaker with age, she is no longer able to view the parades as she once did without Marty’s aid, resigned to simply hearing them. Upon her request, Marty helps her to their porch, withdrawing within their home once again to fetch her shawl. In a turn of terrifying gestural clarity, Marty emerges with the youthful vigour of his cadet days, seemingly emboldened. Sifting through a rosary, Mary seems almost serene as the inevitable arrives- that peace with her mortality, however, is not matched by Marty’s, who finds himself silently wracked with grief. Yet, the parade, which on so many occasions acted as an orchestra commemorating Marty’s ascendancy, does not stop to allow a moment of silence, and it does not and cannot comprehend that his life contains within it boundless tragedy. The parade is a force of nature, thrumming with the hopes and dreams of the young and naive, and elevated to the status of an agent that creates and destroys identity. The parade is a storm of pattering feet and mangled horns, a many-headed beast that pushes relentlessly forward into the future and stamps on the cowardly whimpering of individual agency, a gag in the mouth of any ethical quandaries that may find themselves being voiced by the factory of corpses and MIA letters that is West Point. The parade is death.

The sounds that accompany the nuclear inferno upon which Oppenheimer’s coda is projected are not those of fire searing desert sands or of the screams of those upon whom the bomb was dropped- instead, the sounds belong to dozens of feet stamping rhythmically, as if heralding their obliteration into ashes with patriotic devotion. The funereal parade that ushers us into the fevered imaginings of a young J. Robert Oppenheimer. Not unlike The Long Gray Line, Nolan’s film is framed through conversations taking place decades after the events they deliberate upon have occurred- and, in the vein of Ford’s film, Oppenheimer’s central figure is subject to what resembles an interrogation by one of the highest offices in the country until there are no more truths left to relinquish and no lies left to fill in the gaping void that guilt should occupy. The continuum it unfolds along is not, as one might expect from an artist as committed to the elevation of spectacle as Nolan. Instead, it is one that is defined by the spectacular terror of the Trinity test. The myriad gestures and symbols that Oppenheimer partakes in and embodies, from unionisations of research labs to Presidential awards, may revolve around the nucleus of July 16th 1945, but the weight of every handshake- those accepted and those refused-rings with all the weight of the moment that cemented Oppenheimer in history as “destroyer of worlds”- a title that, like his ostensible affiliations to Communist movements in the USA, is isolated from the near-mythical context within which it exists and is instead construed as a moment in passing that would have catastrophic, unforeseen implications.

The man himself is seemingly incapable of maintaining loyalty to anything except destruction of himself, of others and of the world itself- so of course he is as distanced from the Fordian hero as anyone possibly could be. Yet, when he first assumes the silhouette that could not be mistaken for anyone else, it is framed as an almost triumphant seizing of a grand destiny- as this emaciated figure slides his feet into his shoes, fastens his belt, dons his coat and affixes a wide-brimmed hat to his head, it is as if the simulacrum that is Los Alamos has given birth to a sheriff right out of a Western who, like those within the films of Ford and Budd Boetticher, strut around barren towns and survey the territory for signs of passing. But Oppenheimer is no man of mythos- as the first few images of the film make clear, he is a man guided most persistently by fear, be it of the atom bomb or of the site of creative asphyxiation that is Cambridge. Lame’s cutting, then, proceeds along the continuum of these fears, lingering upon the apple that a young “Oppie” (as he is so often referred to by friends who later turn into enemies) injects with cyanide as long as it does because of how overcome by fear he is at the prospect of his actions having consequences. Rushing to grab the apple from the hand of Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh), then, is not an act triggered by guilt, since guilt would assume the existence of regret independent of circumstance- it is triggered by a sudden and insistent fear that only gives rise to some form of moral reckoning when it is (almost) irreversible. As the trial that he is subjected to by a brutal kangaroo court (composed almost entirely of McCarthyite war-hawks) affirms, this fundamental, existential failure to act- despite their own rabid desire to tear him to shreds clouding our judgement- is no guarantee of remorse. Later on, when something of a celebration tour highlighting the results of Oppenheimer’s work takes place, the opportunity for him to come to terms with the very mortal reality of what he contributed to is sharply dismissed by him tearing his eyes away from a slideshow documenting Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s victims.

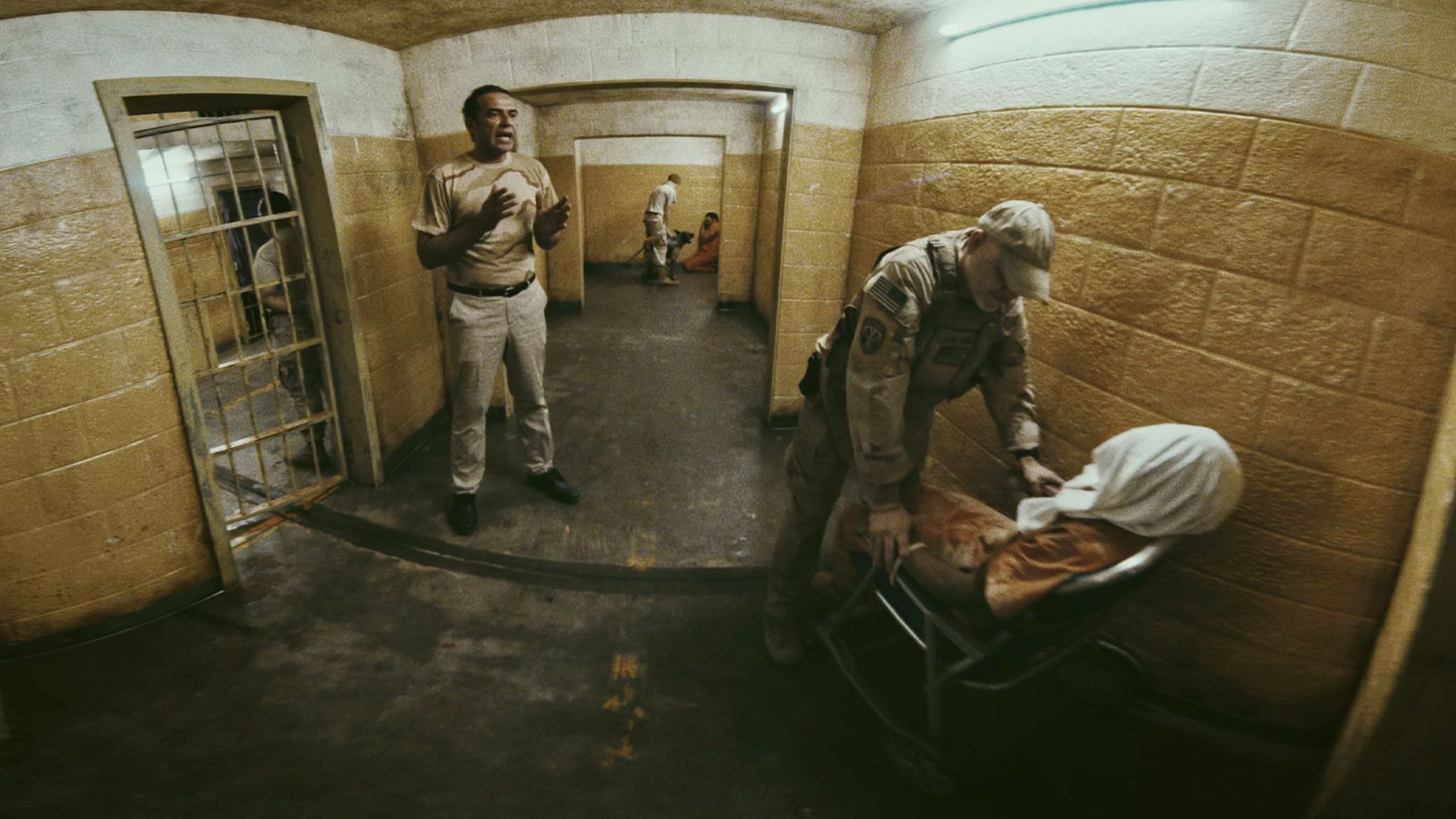

In Paul Schrader’s late-period reckoning with American Original Sin and its engineers, The Card Counter, the titular Bressonian gambler and former war criminal Wiliam Tell (Oscar Isaac) writes in his journal, amongst myriad musings on sin and culpability, the following:

“The feeling of being forgiven by another and forgiving oneself are so much alike, there’s no point in trying to keep them distinct”.

And yet- this dogma, which rings with such weight in the transcendental realm that Schrader operates within- is merely a far-fledged fantasy in the Sispyphean spaces of Oppenheimer, where crucifixion is no guarantee of being absolved, and to be forgiven is an act of humiliation more embittered than having one’s life ripped apart shred by shred for the slightest hint of impropriety. This very naivety is precisely what foregrounds perhaps the most crushing descent of grief upon Oppenheimer’s shoulders in the film- it is a loss that has both everything and nothing to do with the development of the atom bomb. The loss does not settle in, as it gradually does when Oppenheimer presides over a rabidly nationalistic rally and begins to come to terms with the atrocities he has wrought- instead, it is sharp and sudden, penetrating into the musicality of physicists swirling and colliding around the nucleus that Oppenheimer is to the project. When he first hears of the death of Jean Tatlock, it splinters the stream of consciousness that Lame edits with such a jolt that it seems almost subliminal- a glimpse of black leather gloves, a mass of hair falling into a bathtub, ripples emanating from a splash until they finally stop. Her death being reported as a suicide can’t stop the spiral of paranoia that begins then and projects outward until it eats away at his very being, once again disrupting the interrogation that he is subjected to later on. Where the film’s dialectic between the personal and the political is most rigorous, then, is where the boundaries erected between complicity in the personal and political collapse to give rise to a chimera of crumbling egos- from the blood of one on his hands to the blood of hundreds of thousands, a reluctance to speak on one occasion that silences innumerable voices years later and a heat-of-the-moment white lie that affixes the final nail to the cross that he is hoisted on for the rest of his life. What Nolan, seemingly an apolitical filmmaker except for a worrying near-apologia for the Patriot Act in The Dark Knight and an undercurrent of bourgeois liberal rationalism from Inception to Dunkirk, demonstrates with such staggering acuity here is that the very compartmentalisation of the Great Man that enables the long-maintained structure of the biopic is a farce in and of itself when the spheres of the personal and the political are so inextricably intertwined, to the point where the formal delineation between historical fact and fevered paranoia in the film blurs until the two are one and the same.

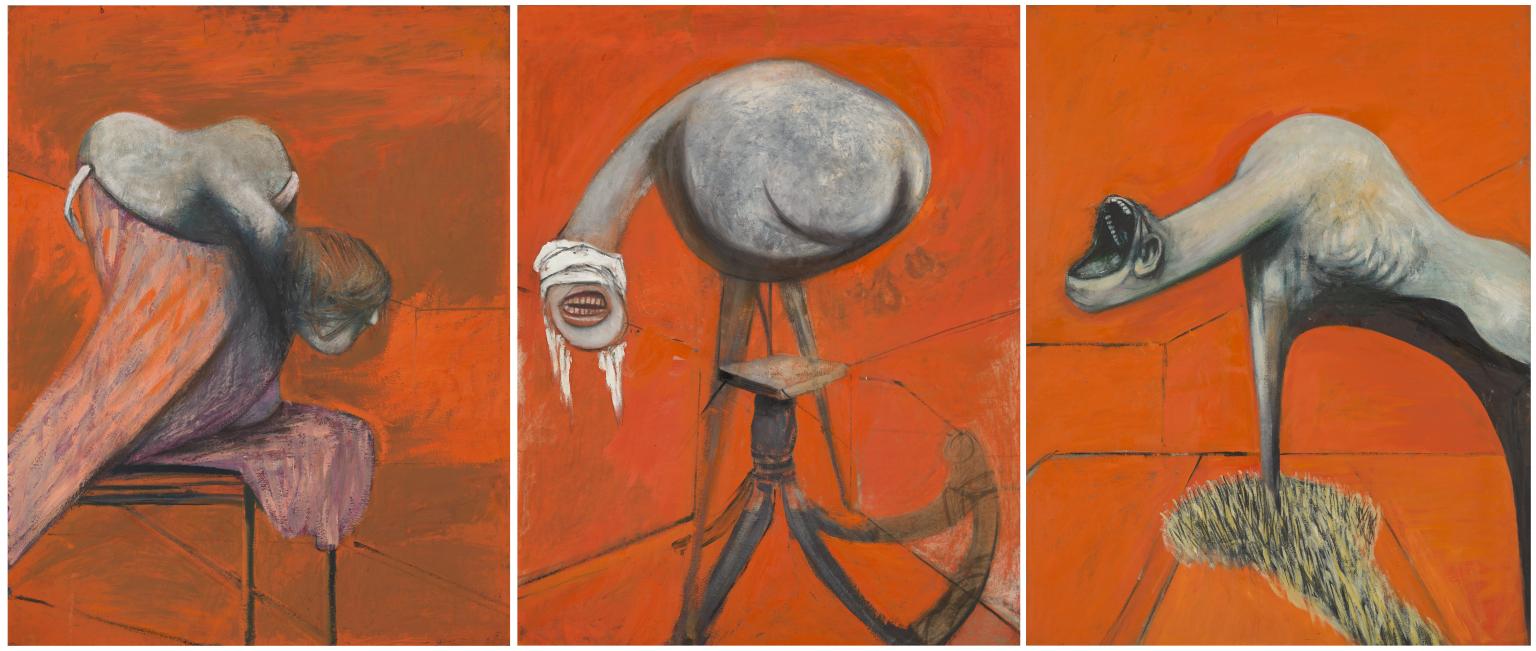

The slamming of fists on tables and of boots against the ground scarcely leave any genuine opportunity for reflection on precisely what the Trinity test yields, since by the time a storm of nuclear fire is wordlessly unleashed in the desert, Oppenheimer and his scientific comrades have already been made obsolete. By the time he is dismissed from President Truman’s office for admitting that he feels he has blood on his hands, Murphy’s rendition of generational genius succumbs almost entirely to an almost desperate naïveté- that is, the fleeting hope that if he undergoes enough self-flagellation, he might find discover the capacity to forgive himself for that most unforgivable of sins. The point at which these hopes are totally and irrevocably shattered, of course, is also the point at which any notions of rigid temporality are similarly obliterated: when he must announce to the families of Los Alamos that the project to which they committed seemingly endless years of their lives has ended with a resounding success. As he takes control of the lectern, a basketball hoop looming above his head cements the nightmarish absurdity of the situation, whereby he resembles less a pioneering physicist than a high school gym teacher, met with a corresponding adolescent glee from his audience. In a fashion not unlike Lynch’s digital experiments Inland Empire and Twin Peaks: The Return, the camera seems to anchor itself around Murphy, as the room begins to shake and blinding flashes of light illuminate his sickly near-transluscent skin. A surreptitious scream echoes across the room as the faces of the crowd increasingly resemble freakish wax masks, and as if held to a flame, begin to melt and peel off. It is a stomach-churningly grotesque pantomime that, in recollection of the recent American cinema, has only really been matched by the often hideous melodrama of Eastwood’s J. Edgar.

But where Eastwood’s political theses (which, like Nolan’s, are often misread as the very subject they are staunch critiques of) are conveyed through chronological accumulation, Nolan’s myriad theses in Oppenheimer are conveyed through Grand Guignol horror that forces you to look it straight in the eyes until you can’t bear to look until any longer. It is a work that forces one to reckon with the recklessly vindictive foreign policy of the United States that has enabled it to act as a genocidal empire within itself since its founding, and externally after WW2, by abandoning the relative comforts of historicity to embody a kind of expressionism that is far closer to Tobe Hooper’s Spontaneous Combustion than anything Nolan has ever done. This is where the Fordian becomes most evident; in the parade that gratifies, there is also a gaping void that can never be filled because there is no guilt to feel it with. Once again, the parade is death.

Since leaving the sold-out screening of Oppenheimer at the BFI IMAX almost two weeks ago, I have been unable to rid myself of the final succession of images that end the film in such a form so as to render me physically ill. In part, it is because the images of nuclear fallout blooming across the Earth like ripples on a pond recall the video transmissions in Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness. In that film, the group of scientists who undertake the risk of examining an ancient artefact hidden underneath a church receive video transmissions from an unknown source- most probably demonic, but the absence of any real shape to those that haunt them is part of what renders them so unsettling. As a hooded figure emerges from a church, zoomed in on by a grainy low-res camcorder, a message resounds:

“This is not a dream... this is not a dream. We are using your brain's electrical system as a receiver. We are unable to transmit through conscious neural interference. You are receiving this broadcast as a dream. We are transmitting from the year one, nine, nine, nine. You are receiving this broadcast in order to alter the events you are seeing. Our technology has not developed a transmitter strong enough to reach your conscious state of awareness, but this is not a dream. You are seeing what is actually occurring for the purpose of causality violation”.

I would like to believe that Nolan’s crowning achievement as an artist is more than simply that, or more than simply one of the only Hollywood films since the 1970s and Beatty’s Reds to seriously reckon with the suffocation of Communism in the USA by resurgent fascist elements of the military-industrial complex. I would like to believe that the unspeakable horrors that make Oppenheimer realise that the entirety of his life’s work has been leading to a nigh-certain apocalypse might induce some sort of miraculous realization of how we exist perpetually on the precipice of nuclear holocaust, in a manner not unlike Terence Davies' Benediction, which similarly ends with the wartime poet Siegfried Sassoon staring through a rain-streaked window with a regret so wounding that it cannot possibly be put into words. In what I considered his prior masterwork, Tenet, Nolan posited the future taking revenge on the past for its murderous irresponsibility in dooming the children of future generations to submersion under rising seas. But that was a film of speculative fiction, one that wrestled with the possibility that there may be weapons more catastrophic than those that exist within the arsenals of every superpower on the planet. Oppenheimer is not a vengeful work of art- it is rightfully full of hatred and contempt for those responsible, and full of sorrow for every Communist murdered and silenced by the government of the United States for opposing the future that has come to pass, but it is not motivated by a desire to undo the past. Instead, like T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (which features so prominently as part of Oppenheimer’s own self-actualization), Oppenheimer is a poem of the post-apocalypse in the truest sense of the term- one that finds in abstraction a source of expressing that its author has seen The End. It is a work that understands that all we can really do now is try and figure out where it all went so horribly wrong, so that the civilization that builds upon our collective ashes might have the foresight to never sow the seeds of their own destruction.