The Card Counter

Originally published on 22/12/21 for the UCL Film & TV Society Journal

A mirror image of many of the traits he writes for his characters, Paul Schrader has grown along with his films. Nearly every film he’s ever directed is fundamentally based on the parable of God’s Lonely Man, an idea that he’s fixated on to the point where entire images and movements dealing with this conceit are recreated wholesale throughout his filmography. At different points in time, these Men have wrestled with demons unique to their particular era of American decay. In First Reformed, it was climate change and our irrefutable responsibility for the destruction of the planet. In The Canyons, it was the image itself, imbued with the toxicity of the Hollywood environment in which it was created. His latest film, The Card Counter, may be structurally similar — eerily similar — to his earlier films (particularly Light Sleeper), but tonally, it has much more in common with his late-period oddities Dark and The Canyons than it does with his more uniformly serious work.

Schrader’s muse for this latest entry in his saga of the collapse of interiority is Oscar Isaac, whose rugged, chiselled features match the fractured psyche of the tortured veteran he plays, William Tell. The cycles of ritual that surround Schrader’s protagonists live on here, the camera acting as a passionless observer of Tell’s routine. It follows him through functionally identical caverns of capital; shoddily lit, cramped rooms where those seeking thrills or a financial lifeline gamble away their futures. For Tell — and by extension, Schrader — there’s no tension extracted from the card-playing sequences here, nor do they act as fundamental influences. It isn’t so much the act of gambling that the camera focuses on, as much as it’s the expressions of those playing it, which remain almost entirely static. Schrader’s concerns here have nothing to do with poker because, for both him and Tell, it seems to be a fleeting distraction, something to keep one’s hands busy, rather than something of value.

Unlike Blue Collar, dollar bills exchanged over tables here represent little more than a footnote to Tell’s passionless career as a poker player. Instead of criticizing the endeavour of gambling as a cog in the capitalist superstructure, Schrader presents a hypothesis far more unsettling; that it doesn’t matter because it acts as an escape from things much worse.

That implication is where the wider concerns of this text begin. Through a fisheye lens, dizzying VR sequences fly through torture chambers and the minds of the men that inhabit them, both perpetrators and victims. Here, the piercing qualities of Schrader’s script translate to wordless brutality; sequences of indescribable humiliation and flashes of violence that seem to exist in a heightened version of reality, despite being based on very real events. An indictment of the American military-industrial complex has been crucial to past entries in Schrader’s oeuvre, but the candour with which The Card Counter confronts the complicity of the individual in this engine of death renders it distinct among the rest of his Bressonian texts. His concerns with Catholic guilt and absolution are maintained, but as opposed to the search for redemption and a slow, toxic discovery of the truth in First Reformed, it’s clear early on in this film that there are no illusions as to Tell or anyone else’s responsibility. By framing the trail of blood spilt by the American military solely through Tell’s various lively anecdotes and fever dreams (in which Willem Dafoe acts as a nigh-omnipresent Cerberus to the Hell that is Abu Ghraib) the film avoids falling into the cycle of apologia that characterizes much of the cinema that tackles post-9/11 American imperialism. Perhaps the aspect most telling of the film’s thesis on imperialism is the introduction of Cirk (played by Tye Sheridan), a young man indirectly implicated in the very evils that Isaac’s character partook in. There’s an inherent contradiction in Cirk’s, and most criticisms, of the Bush and Obama era’s torture programs; that the soldiers who partook had no choice and are victims of the institution just as much as those they tortured. Isaac’s dreams and intermittent monologues, however, reject this notion:

“He wanted to. Just needed an excuse”.

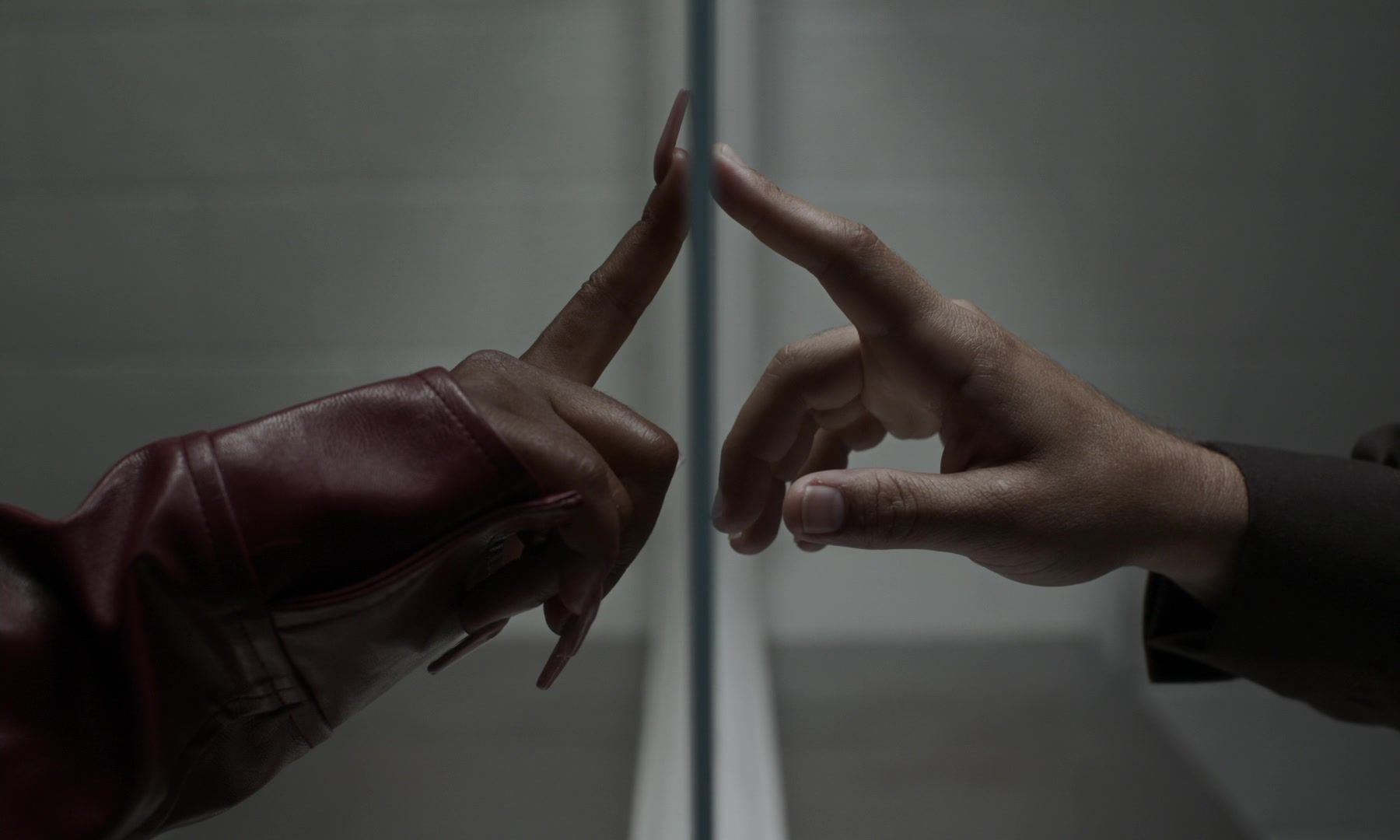

Rather than isolating Tell in a vacuum of self-pity, there’s a pointed contrast between his mechanical, fringe performance and the relative normalcy of his co-performers. Tiffany Haddish, playing the enigmatic backer La Linda, operates on an entirely different wavelength compared to Isaac. As per many of the directorial decisions that characterize Schrader’s work, this performance is initially a befuddling one in that it is defined by levity rather than the weighty nihilism inherent to Schraderian protagonists, especially in one of his gloomiest works yet. To the contrary, however, I’d argue that Haddish’s performance is a perfect counterpart to Isaac’s precisely because it reflects a degree of stability and charm that seems entirely out of the purview of a character as weighed down by his past as Tell. She acts as the film’s beating heart, a twinkle in the corner of Tell’s eye just as fascinated by him as he is by her. The relationship that develops between them is peculiar and predicated on the basis of a transaction, but in the cold, impersonal vision of postmodernity Schrader crafts here, any form of connection, no matter how unstable, is better than none.

The construction of space and the ways in which characters navigate it is another one of the conduits through which The Card Counter conveys its sharply political thesis. Every interior is virtually the same, populated by flashing slot machines, dimly lit poker rooms, and featureless hotel rooms. Everything is draped in the haze of neon and white sheets as if to cover up the blood on the hands of those who touch them. Tell is virtually a ghost, wandering through the corpse of small-town America as a scalpel moulded to tear through bone and muscle, but with little else to do. The nigh-monotonous nature of the poker games played by Tell is far from a mark on the film’s narrative; instead, the repetition of the same hands of blackjack, the same stale coffee and the same sleepless nights acts as a polar contrast to the sinister plot constructed by Cirk, into which Tell is inevitably drawn. It’s a ticking time bomb, existing only in the slight facial twitches and barely noticeable tremors of rage exhibited by Tell, until the brutal, bloody, and maybe even cathartic climax.

It’s undeniably Schrader through and through, but age and the tides of political change have added a nastier edge to his commentary on institutional decline. For perhaps the first time, this is a Schraderian treatise on redemption that outwardly rejects any possibility of it, seeking only refuge in the mortal world. This is a quintessential American director at his grimmest yet most clear-eyed, making The Card Counter one of the very best films, if not the best film of the year.