‘Watchmen’ revisited

Originally published on 12/09/2019 for the Daily Times.

In an era where cinematic adaptations of comic books and graphic novels starring spandex-clad übermenschen are released like clockwork, with barely, if any, consideration for thematic undertones, and attention to aspects of filmmaking. The state of their source material shows is little better than their adaptations; monthly editions of comic books distributed by the two monopolies in the industry, Marvel and DC, revolve around crossover events involving the forced intersection of multiple storylines, as a method of promoting themselves to potential customers. Furthermore, the unfathomable success of Disney’sAvengers: Endgame, little more than a 3-hour long, perplexing assemblage of overused corporate properties and fan service, is proof of an ever-encroaching creative monoculture that stifles any chance of success of original properties; it can be easy to forget that comic books were once considered to be a niche industry, with minimal potential for expansion.

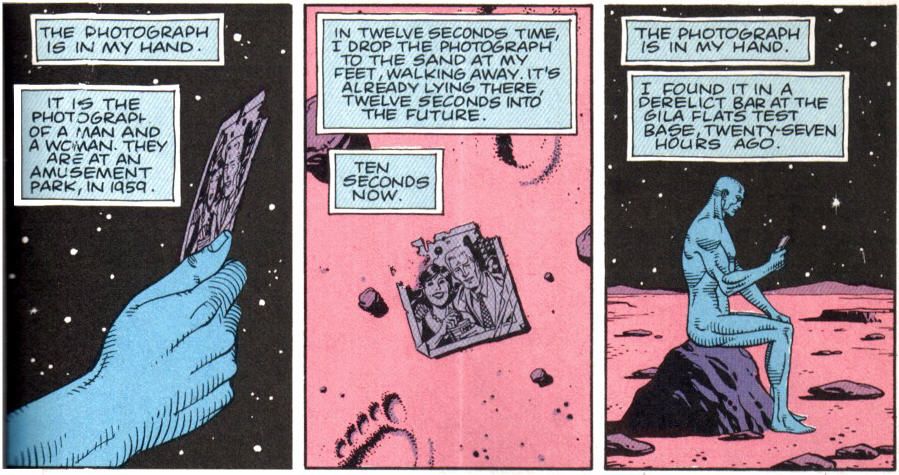

Yet, 33 years ago, the very definition of what a comic book could be was irrevocably altered with the publication of Watchmen, which is being loosely adapted for an upcoming HBO television series.

Watchmen, written by acclaimed writer Alan Moore, drawn by Dave Gibbons and coloured by John Higgins, was first conceived of in 1983; Moore, who began his career writing for British fan magazines, and later comic strips was hired by Marvel’s UK division in 1982 to work on the series Marvelman. Initially described by Moore as “a superhero Moby Dick”, Watchmen endured a series of delays, with the book being written in chapters; when issue five was on store shelves, Moore was still writing issue nine.

On its release, Watchmen’s critical reception surpassed even Moore’s expectations; Time termed it as being “by common assent the best of breed” of the line of comics at the time, and praised it as “a superlative feat of imagination, combining sci-fi, political satire, knowing evocations of comics past and bold rewordings of current graphic formats into a dystopian mystery story”; it was later added to Time’s List of the 100 Best English Novels. In 1988, Alan Moore was awarded an Eisner Award for Best Writer; the same year, Watchmen was given a Hugo Award for Other Forms.

Zack Snyder’s Watchmen adaptation premiered in 2009; and now, a decade later, HBO plans to release a sequel to the original in the form of a television series.

Along with The Dark Knight Returns, Watchmen ushered in a generation of “grounded” storytelling in graphic novels, with a greater emphasis on socio-political elements, that continue to maintain their thematic relevance today; revisiting Watchmen in 2019 makes it easy to see why.

Watchmen opens not with an unravelling of cosmic proportions like most “event” comic runs, but with a murder, intercut with the narration of an entry from the diary of one of its protagonists, Rorschach. Rorschach is a prime example of how Watchmen differs from its contemporaries; he is an experiment in what the typical antihero vigilante archetype would be viewed as in the real world: an unhinged criminal. His repugnant views and brutality are intended to repulse readers; yet, his black-and-white moral philosophy and refusal to compromise renders him, in some aspects admirable. The murky investigation he begins in the opening of Watchmen serves as the focal point from which a more sinister conspiracy branches, placing Rorschach at the plot’s epicentre.

Conversely, Ozymandias is introduced as Rorschach’s polar opposite; a Superman-archetype with prodigious intelligence, who’s public identity is that of a benevolent philanthropist.

Another one of the many factors as to why Watchmen retains its relevance today is its background; written shortly after the end of the Cold War, Watchmen takes place in an alternate timeline where the Cold War is at its peak in 1981, and the dreaded Doomsday Clock is 5 minutes from midnight; the shadow of imminent nuclear war looms over the story, with a heightened sense of paranoia influencing the characters. Yet even today, when the United States and Russia are on far friendlier terms, the threat of Armageddon persists; rapidly escalating climate change and tense foreign relations have formed an atmosphere of mistrust to the same extent as decades prior.

“I did it thirty-five minutes ago”.

The fear and hysteria of imminent Armageddon are manifested in alarming detail in Watchmen’s climax; an intricate scheme to discredit and assassinate costumed vigilantes unfolds into a generation-spanning conspiracy, with a disturbing ultimatum; genocide. As the story progresses, Rorschach, along with a retired ally, Nite Owl, discover that in order to end the Cold War and unite the US and Russia, Ozymandias has planned to unleash an Eldritch horror to unify the world’s superpowers: a colossal, psychic squid in the vein of Cthulhu that would telekinetically annihilate millions. As the duo travel to Ozymandias’ headquarters to halt his seemingly ridiculous plot, they discover a terrifying truth: in contrast to the cliché of the triumph of spandex-clad heroes over moustache-twirling villains, Ozymandias, anticipating an attempt to abort his plot, triggered his genocidal attack in multiple cities 35 minutes prior to the protagonists’ arrival. The imagery of Ozymandias’ abomination looming over the corpses of millions in New York remains haunting, even today. Ultimately, Ozymandias plan unites billions, but at the cost of millions; a utilitarian achievement necessitating a lack of a moral compass.

Watchmen, even 33 years later, defies norms and acts as a prescient philosophical deconstruction of our fascination with comic books and the characters that inhabit them, and a fatalist critique of Cold War politics. The central question Watchmen demands an answer from its readers to is this: can compromise ever truly lead to resolution? As Rorschach utters at the story’s end:

“No. Not even in the face of Armageddon. Never compromise.”